A decade ago, smart cities were predicted to be just around the corner. And they still are.

Urban planners, technologists and city leaders have trumpeted a few pilot projects and made glorious promises of driverless shuttles, connected streetlights, leakage-detecting water pipes, super-resilient energy grids. and smart electric meters.

Take Barcelona, one of the first smart city initiatives, for instance. When the city announced plans for its smart campus in 2011, it was working on pilot projects to install an urban platform of sensors to monitor everything from waste collection routes and parking spaces, to gas, electricity and water usage in homes. Their vision was to create an integrated platform of connected devices and leverage the massive amounts of data collected for more efficient management of the city.

Cut to today. Practically every other week, a new city announces plans for using smart city technology. The arrival of 5G and faster Internet of Things (IoT) connectivity promise to entice even more cities to embrace the power of digital data to improve humans’ lives.

But all of that is still on the horizon. Today, smart cities are still largely in the aspirational stage. Sure, there have been some high-profile projects, but what we’ve most often seen deployed are one-off applications of solutions that focus on just specific issues, such as parking, lighting, or traffic management. The grand vision of a holistic end-to-end networked smart city has not yet been realized.

Millions of sensors do not a smart city make

Here’s the reality about smart city projects today: they are few and far between. Two out of every three projects implemented in the U.S., for example, are either trials or only cover parts of the city, according to HIS Markit.

“There is a long tail of cities focusing on specific issues or looking for cross-departmental transformation on a smaller scale,” observes Serena Da Rold, program manager in IDC’s Customer Insights & Analysis group.

Da Rold has a point. Even cities like Barcelona, that started their journey almost a decade ago, are now rethinking their smart city projects. In fact, Francesca Bria, Barcelona’s chief technology officer, is now promoting a strategy for digital sovereignty — aiming to take ownership of all the city’s projects and to create an open-source sensor network with common standards, connected to a platform owned and managed by the city.

But, to Barcelona’s credit, they have also been making progress to enable myriad designs in the works. The city has, for instance, designed a platform called “Sentilo,” meaning “sensor” in Esperanto, to share information between disparate heterogeneous systems, so that data on different dashboards of various projects can talk to each other seamlessly.

While smart city development has been slow, interest continues to grow. As of two years ago, two-thirds of local governments had invested in smart city technologies, according to a National League of Cities survey conducted in 2017. And now, IDC forecasts worldwide spending on smart cities initiatives will reach $95.8 billion in this year, an increase of 17.7 percent over 2018.

There are also an increasing number of tech companies innovating new smart city solutions. More vendors were listed as selling smart cities technologies than gaming and fitness products combined at this year’s Consumer Electronics Show.

Cities need the tools to put data to work

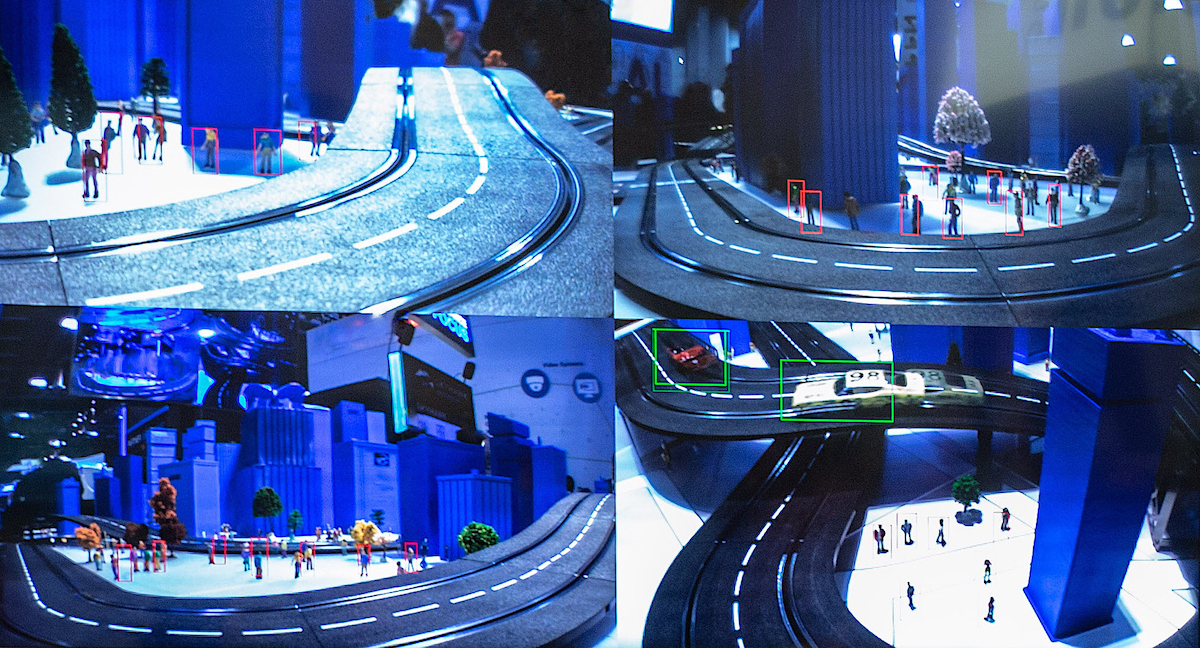

Despite a decade-long push by government and business leaders, why does it seem that smart cities are stuck in the slow lane? One explanation is that deriving value from a smart city depends on more than a network of connected IoT devices. Cities will need to be able to implement the infrastructure, systems and capabilities like artificial intelligence (AI) to manage and help decipher the avalanche of data they collect into actionable next steps.

Despite a decade-long push by government and business leaders, why does it seem that smart cities are stuck in the slow lane? One explanation is that deriving value from a smart city depends on more than a network of connected IoT devices. Cities will need to be able to implement the infrastructure, systems and capabilities like artificial intelligence (AI) to manage and help decipher the avalanche of data they collect into actionable next steps.

After grappling with one-off projects for years, several cities are beginning to explore robust data management and analysis solutions to standardize and analyze their data. The Smarter London Together program in the UK, for example, is working on improving data-sharing of information related to the city’s public services. London’s nine-year old Datastore is now a free and open portal, where anyone can access data relating to the city.

To help cities in their quest for comprehensive data systems, several organizations are creating digital platforms to consolidate and standardize services that improve urban planning. For example, Surveyor, a tool created by Coord, uses augmented reality to collect accurate imagery information from road signs at curbs in order to provide more accurate parking information to drivers in real-time and enable policy makers to tweak curb regulations to be better suited for drivers.

Similarly, the National Association of City Transportation Officials has created SharedStreets to provide a global non-proprietary system for describing streets. The SharedStreets software platform creates a structured language for digitally describing and linking places on a street, enabling city planners and transportation companies to easily share information and collaborate to manage traffic.

Important challenges must be addressed (Who controls my data?)

As cities get better connected, and collect more and more data, they face huge privacy and security questions. Community leaders and residents are asking what data is being collected, how is it being used, who gets access to it, and who monitors it? To allay these important concerns, some cities, such as London and Toronto, have set up data trusts — a legal structure that provides independent stewardship of data. These trusts are expected to gather and manage all the data collected by various networks of IoT devices in the city and set conditions on how to share this data with various public and private sector shareholders.

Establishing a data trust, however, can be fraught with complications. Sidewalk Labs, an Alphabet company, has, for example, set-up a trust in Toronto. The trust will manage all the data collected from the modular buildings, utility grid devices, and on-street sensors that the company plans to build in a “smart” neighborhood in the Quayside section of the city.

Despite SideWalk Labs’ efforts, the Quayside project has faced strong resistance from locals. A SideWalk Labs consultant, Ann Cavoukian, the former information and privacy commissioner for the province of Ontario, raised concerns that the plan didn’t require the trust to ‘de-identify’ or anonymize data at the source.

Sidewalk Labs, however, maintains that it doesn’t want to control or own the data. Decisions related to managing and anonymizing the data, the company says, should fall to the trust. That might be a reasonable approach, but some Toronto residents are not yet satisfied and have launched an online campaign to raise awareness and prompt action on such issues. Skepticism and criticism in Toronto suggest that no conversation around sensors and data collection in other cities will be complete without addressing privacy concerns.

While recognizing there are challenges, more and more cities are deploying IoT networks to optimize their infrastructure and improve quality of life in a world that is becoming more and more urbanized. Over two-thirds of the population is expected to live in cities by 2050, according to UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

One thing many cities agree on is that technology will help support this new wave of urban citizens. According to a McKinsey Global Institute report, Smart cities: Digital solutions for a more livable future, cities that deploy smart applications can reduce commuting times by 15-to-20 percent and reduce fatalities, from homicide, traffic accidents, and fires by 8-to-10 percent by 2025. Optimized dispatching and synchronized traffic lights also promise to cut emergency response times by 20-to 35-percent, the report adds.

Why the rise of the edge is critical to the birth of smart cities

Fast-expanding IoT sensor networks, 5G wireless infrastructure’s blazing fast data rates, and AI tools promise to help realize the dream of smart cities.

A critical factor will be the continued development and large-scale deployment of the edge computing infrastructure, which enables millions and millions of sensors embedded in building, cars, traffic lights, parking meters and the energy grid to process information and analyze data where it is collected, rather than sending it to the cloud for processing.

Autonomous cars, for instance, will generate and consume an estimated 4000 gigabytes of data for every eight hours of driving. Millions of other IoT devices on smart city networks will collect equally large amounts of data. The amount of bandwidth required to send that data to the cloud is immense, and could clog communication pipes that connect to the cloud infrastructure. By enabling data to be processed closer to where it’s created, edge computing reduces the need to transfer data back-and-forth.

According to Seagate’s recent report Data at the Edge, self-driving cars need to make life-and-death decisions in a split second, and can’t wait for data to be sent the cloud. “While humans might be willing to wait hundreds of milliseconds for data to travel from our smartphones to a centralized data center thousands of miles away, many machine-to-machine applications don’t have that luxury,” notes the report.

An evolution toward the cities of tomorrow

Most cities began their smart city initiatives by adding sensor networks to improve a specific service at a time. But, the promise of IoT and robust data management practices is paving the way toward a more streamlined digital infrastructure. Connected buildings, roads, streetlights, power grids, and utilities are coming.

City managers and planners are already using new technology that will help them realize the promise of converting a continuous flow of big data into action that improves the quality of life for their residents. Although it may be a few blocks yet before we arrive, we can certainly say the era of smart cities is just around the corner.